Behind the Scenes at the Opera

Simon Rees hosted the above study day in March of this year. Feedback from those who attended and completed evaluation forms overall found the day fun and highly interesting. One re-occurring comment was ‘a polished performer… very entertaining. Enjoyed his personal insights and experiences at The Welsh Opera Company’. Another attendee said that this day had inspired him to attend more operas.

15 evaluation forms were completed on the day. Six evaluation forms were received by email. The following comments were made about the facilities:

- Room needs to be set out better to aid acoustics x 4 people.

- Water needs to be available for attendees and speaker more readily x 2 people.

- Heating tended to go up and down throughout the day. X3

- Lunch was good but the quiche needed improving! X4

The above has been fed back to Paul the manager at The Whitworth and he says he can make the changes as requested. Plus there will be a new and exciting lunch menu this autumn courtesy of a new chief.

From Sherlock Holmes to Hercule Poirot and Lord Peter Wimsey

2nd November 2021

We were treated to two brilliant lectures by Richard Burnip who is an actor, writer and historian of the theatre. Richard is a long-standing Arts Society lecturer and he has a wealth of knowledge on his subjects. This study day gave him the opportunity to expand on two generations of detective fiction and how these were taken from the page to the screen.

Richard began by giving us tremendous insight into Arthur Conan Doyle’s background as a GP and his inspiration for Holmes from his old mentor, Dr Joseph Bell. Bell was a surgeon and lecturer at Edinburgh University famed for his powers of observation and deduction in diagnosis. His observations in revealing the backgrounds of his patients inspired Doyle to attribute such qualities to Holmes.

Whilst still practising as a GP Doyle wrote his first Holmes story, a ‘Study in Scarlet’ in 1887. It was not a huge success and eventually appeared in Beeton’s Christmas Annual. Doyle only wrote four full novels, all the other well-known stories were short and appeared in magazine form between 1890-1899.

Very early on the stories (ostensibly written by his friend Dr Watson) were short episodes that appeared in the magazines. Early illustrations were done by Charles Doyle, Arthur’s father. Notably the ‘Sign of Four’ in 1890, which appeared in Lippicott’s magazine, was written in a single month. Thereafter short stories about Holmes exploits appeared in the Strand Magazine and were handsomely illustrated by Sidney Paget. Doyle and Paget brought Holmes to life and he was seen with a variety of hats and pipes. Paget set the image of Holmes in all his disguises and together with Doyle’s brilliant tales, they formed the image of Holmes we have today.

In the 1890s copyright was fragile and directors were beginning to put Holmes on the stage. Holmes was often portrayed by the actor Henry Irving, a master of disguise, who was able to develop the character and persona so well known today. Over the years Holmes has been portrayed by numerous famous actors including, William Gillett, Harry Saintsbury, Lionel Barrymore, Basil Rathbone, Jeremy Brett and Benedict Cumberbatch. All have brought their own interpretation to the role.

In 1893 Moriarty first appeared and caused the ‘death’ of Holmes in the ‘Final Problem’. Doyle then wrote other things and also went to the Boer War as a doctor. On his return in 1903, he brought Holmes back to life in ‘The Return of Sherlock Holmes’ and ‘The Empty House’. Between 1903-1914 Doyle wrote more short stories which were brilliantly illustrated, often in colour.

Following the First World War Doyle devoted much of his time to the cause of Spiritualism. But he was tempted back to writing about Holmes in the 1920s, though all the stories are set in the 1890s. 1927 saw the last new story in the Strand magazine and in 1929 Saintsbury did his final stage tour. Doyle died in 1930, leaving the legacy of the most famous fictional detective ever known.

Agatha Christie and Dorothy L Sayers

The two most famous female crime writers of the pre-war era, Christie and Sayers created two of the most loved and admired character detectives in the form of Hercule Poirot and Lord Peter Wimsey. Richard’s second lecture centred on these two wonderful characters and in particular those areas of London most inhabited by them. Richard took us on a visual tour of Mayfair and St James where these characters lived, worked and played.

Between 1932 and the 1940s Sayers wrote several LPW novels and about 20 short stories and gradually introduced familiar characters such as Harriet Vane and Bunter. In 1932 Sayers wrote ‘Have His Carcass’ in which we first meet M’Lord. We follow his butler, Bunter, into a cinema in Haymarket and Richard showed us the probable location.

Sayers had a flat in Dover Street and knew all the clubs in St James. It is probable that ‘The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club’ was situated at 94 Piccadilly in the Naval and Military Club and LPWs new flat was probably on the sight that is now Park Lane Hotel and South Audley Street is almost certainly the location for the ‘mysterious woman’.

These characters too have been portrayed on stage and screen most notably Ian Carmichael and Edward Petherbridge. Both of these actors would know South Audley Street and the St James Clubland well. Harriet Vane first appeared in ‘Strong Poison’ and has also been played by Constance Cummings and Veronica Thurleigh on stage in 1936 and Harriet Walters on TV in the 1980s.

Agatha Christie, probably the most prolific crime novelist of all time wrote dozens of novels and short stories featuring Miss Marple and Hercule Poirot. She sold the film rights of the Marple novels to MGM and this resulted in several ‘awful’ films starring Margaret Rutherford as the aging spinster PI. Christie also wrote ‘The Mousetrap’ which is still the longest running play in the West End. With a brief gap during WW2 it has been running for over 70 years.

Christies characters also feature in Mayfair and St James and ‘Sleeping Murder’ 1940 brought Marple to the Haymarket theatre. In ‘The Secret Adversary’ Tommy and Tuppence met at Dover Street Station. Although this no longer exists as an underground station, the frontage is still identifiable on Dover Street. Arlington House on Arlington Street SW1 is probably the venue for Poirot’s flat.

Her model for Bertram’s Hotel is probably Flemings Hotel in Mayfair where Christie stayed as a young girl. It is tiny and has not changed much during the twentieth century. And ‘Hays Mews’ which features in ‘Murder in the Mews’ is probably modelled on Bardsley Garden Mews. Poirot would have been right at home in Chesterfield House, near Audley Square, where he could have consulted with Lord Peter and Harriet.

What a treat we had. We roamed around late Victorian London and then were escorted through the high echelons of society through Mayfair and St James. Thank you, Richard, for the most entertaining morning.

Sylvia McKenzie

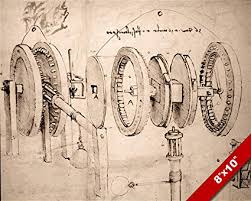

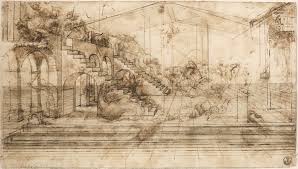

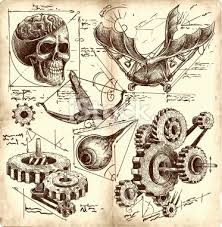

The Genius of Leonardo da Vinci

16th October 2019

To most of us, Leonardo da Vinci is regarded as a renowned painter and sculptor and yet, in reality, his talents and interests went so much further: anatomy, war machinery, architecture, water engineering, aerodynamics and botany. It was interesting that our Study Day was led by a retired surgeon rather than an art specialist.

Leonardo da Vinci, an illegitimate child, was born in a small village between Pisa and Florence in 1452 and raised by his grandmother. He had no formal schooling and spent a lot of time in the countryside around his home, studying nature and drawing. He was never without a notebook and drew everything he saw with explicit notes alongside all executed in mirror writing. At the age of 17 he was apprenticed to Verrochio in Florence where it was apparent very early on that he had great talent. He came to the notice of the Medici family and received commissions. At the same time he became interested in the structure of the human body and attended dissections where he made copious anatomical drawings. Whilst there are around 15 – 20 oil paintings currently attributed to da Vinci, there are over 7,000 drawings in existence.

In 1480, he moved to Milan to work for the Sforza family promoting himself primarily as a war engineer, designing all manner of war machinery.

He did, however, continue painting and it was during this period that he painted ‘The Virgin of the Rocks’ and ‘The Last Supper’.

For good measure, he also tried his hand at architectural designs, though none of these were ever constructed.

He returned to Florence in 1506 where he was appointed Water Engineer and was charged with making the river Arno navigable from Florence to the sea. Responding to the need to raise and lower boats, he invented the first lock, the design of which has barely altered in the last 500 years. His interests were inexhaustible: he studied flight by watching birds and designed a basic parachute and helicopter; he explored map making and marine architecture, designed machinery and created the first ‘exploding’ drawings for engineers.

It was here he painted the ‘Mona Lisa’ and his final painting, ‘Leda and the Swan’.

All the time he continued his anatomical drawings and so accurate are they that many of these are used by medical students today. In his later life, he was particularly interested in embryonic development and made many drawings of embryos at different stages of growth. The Church at the time was violently opposed to these drawings and he was reported to the pope where he fell from favour.

By this time, he was an old and frail man, and he was invited by the French king, Francois 1er, to come to Amboise in France where he died in May 1519.

By the end of the Study Day, we had learnt of the full range and talent of this incredible man: artist, sculptor, engineer and designer. Unquestionably, he certainly was a genius.

ELIZABETH WETHERALL

WILLIAM MORRIS AND BURNE-JONES: DEVOTING THEIR LIVES TO ART

10TH April 2019

In a highly informative day, Dr Suzanne Fagence-Cooper brought a clear perspective to the way in which Morris and Burne-Jones, both in collaboration and separately, brought their approach to art to change the development of the decorative arts in the late nineteenth century.

To understand their achievements, it is necessary to consider the key contributors to nineteenth century art history and the atmosphere at the time. Above all was the influence of Ruskin and his views that the ‘teaching of art is the teaching of all things’ and the importance of collaboration: ‘no work of art is by a single man/woman’.

The lifelong friendship and collaboration between Morris and Burne-Jones existed despite them coming form very different backgrounds. Morris came from a wealthy family and had a private income, whereas Burne-Jones was more of a realist as a result of a working-class upbringing in Birmingham. When they met at Exeter College Oxford in 1853, they were destined for careers in the church, but they were subjected to many influences which drew them to art and the relationship between man and heaven. Burne-Jones felt that ‘heaven starts 6 inches above our heads’. Angels featured in many of his early works and in later commissions for churches. He considered them to be androgynous and was criticised for depicting them as too manly for a woman and too feminine for a man.

Early influences were Oxford and its cloisters and college chapels and Ruskin’s view which sought to establish the relationship between the actual world and the gothic. After a walking tour in northern France, Morris and Burne-Jones decided against the church and in 1855 decided to ‘dedicate ourselves to art’.

Morris was able to undertake further education in architectural studies, Burne-Jones, with no formal artistic training attended the Working Men’s College. There he met Ruskin and Dante Gabrielle Rossetti, who were his tutors. This college was unique at the time, delivering lectures to women as well as men. There Burne-Jones learnt the value of looking back at the works of the past and was especially influenced by the asymmetry of the Ducal Palace in Venice and the paintings of Fra Angelico and Jan Van Eyck.

The first major collaboration between Burne-Jones and Morris was the debating chamber at the Oxford Union. They painted Arthurian legends, which have deteriorated badly due to their lack of knowledge of mural painting. Their inspiration came from the 13th century Mallory’s Morte D’Arthur.

Their other collaborations came from Jane Burden, an embroiderer (who later married Morris in 1859) and became their muse for Guinevere. She inspired Morris to write his poem ‘In Defence of Guinevere’. They had two daughters, one of whom worked with Janey to produce beautiful embroidered designs for Morris’s textiles. Burne-Jones also married and his wife Georgie made her own career in woodcuts.

The 1850’s and 1860’s saw an upsurge of industrial design, partly inspired by the Great Exhibition of 1851. Morris perceived it as representing only functional design, but nevertheless it helped encourage wider opportunities for design in the home. The newly married Morris moved out to Bexley Heath to avoid the widespread disease in London and there he and the architect Philip Webb created the Red House, with its asymmetrical design. It created a place for experimentation in home furnishing, including Morris’s designs for fabric, wallpaper and furniture, in which Janey collaborated. They formed Morris and Co and encourage other artists to design beautiful items for domestic use.

Their artistic circle continued, with Burne-Jones and Georgie joining Morris and Janey at the Red House and later at Kelmscott Manor. Rossetti also joined them and used Janey as his model for many of his works and they became lovers. Morris meanwhile, was driven by his need to work and accepted the affair, which ended when Rossetti became addicted to opioids. Kelmscott became a place of retreat for artists and Janey remained there all her life, after Morris’s death in 1896.

Morris revived the art of stained glass and Burne-Jones turned much of his attention to creating some of the most beautiful and iconic piece of work in churches throughout England. In 1896, after several years work, the Kelmscott Chaucer was published, with illustrations by Burne-Jones, featuring asymmetrical borders. Their collaboration was so intense, that when Morris died in 1896, Burne-Jones said it was ‘like the halving of his life’. He only survived until 1898.

Thus Dr Fagence-Cooper ended our study day which had covered one of the most important periods of change for decorative arts, and all who attended gained from the extensive knowledge of such a distinguished art historian.

Keith Horncastle